‘Spain, the Eternal Maja': Goya, Majismo , and the Reinvention of Spanish National Identity in Granados's Goyescas

Walter Aaron Clark

Among the best-known Spanish

piano works is Goyescas by Enrique Granados, a

suite of six pieces in two books inspired by the art of

Francisco Goya and composed between the years 1909 and 1911.

The composer's fascination with Goya was shared by many

writers and composers in Spain around 1900, and this fascination

has wider resonance in the political culture of the time.

This paper briefly surveys the phenomenon of majismo

in Granados's late career and the role it played in

the reinvention of Spanish national identity around 1900.

A great debate raged in Spain

in the 1890s and early 1900s, centering around the nation's

place in the world, its identity and future. In the latter

part of the nineteenth century, conservative politicians

such as premier Antonio Cánovas del Castillo promoted

xenophobia and fueled distrust of foreign influence, at

the same time asserting that Spain was a major power and

had an important role to play in the world. Spain's defeat

in its war with the U. S. in 1898 made it more difficult

to embrace such a fantasy. Illusions of national grandeur

proved unsustainable in the aftermath of such a humiliation

and the loss of the remnants of a once-vast empire.

In response to this crisis,

the fundamental question arose, "Should Spain recast herself,

importing from [northern] Europe all the trappings of ideology

and material progress, or should Spain retrench to her traditional

self, casting aside liberalism, as well as economic and

technological values?"1

In more simplistic terms, this was a choice between conservative

and liberal politics, between religion and science, between

the Siglo de Oro and the Englightenment, between

apparently irreconcilable opposites that had clashed before

in Spanish history and would culminate in a ruinous civil

war and decades of right-wing dictatorship later in the

twentieth century. These were the issues that preoccupied

a number of writers collectively known as the Generation

of '98.

Then again, maybe this was

an artificial dichotomy. Perhaps there was a third way.

In his 1895 essay En torno al casticismo ("On

'Casticism'"), Miguel de Unamuno, one of the leading writers

of the Generation of '98, found a solution that came to

exercise a profound influence on artists and intellectuals

in the wake of the Spanish-American War. Casticismo

means "genuine Spanishness," the pure spirit of the

nation, implying a reverence for tradition. Such a term,

of course, is slippery enough to be capable of almost any

definition, and some used it as a shibboleth in denouncing

foreign ideas and trends. That was not Unamuno's approach.

He rejuvenated the notion of casticismo, and from

his point of view, "Spain remains still undiscovered, and

only will be discovered by Europeanized Spaniards." 2

Unamuno believed that Spain

could, in a sense, have its cake and eat it too, that it

could Europeanize without abandoning its unique identity.

Of course, Spain was already a European nation, but by "Europe"

'98 writers in general were referring only to the most advanced

and powerful countries, namely, France, Germany, and England,

whence came the most influential trends in science and the

arts.3Spain

was perhaps a decade or two behind them in terms of its

overall development. In En torno al casticismo,

Unamuno declared with justification that "Only by opening

the windows to European winds, drenching ourselves with

European ambience, having faith that we will not lose our

personality in so doing, Europeanizing ourselves to create

Spain and immersing ourselves in our people, will we regenerate

this treeless plain."4

France served as something

of a model for the Generation of '98, because it, too, had

undergone a crisis of national humiliation in the Franco-Prussian

War of 1870-71, which had shattered its illusions of military

and cultural superiority. The defeat led to an interest

in monuments and museums as emblems of the nation's former

glory. And the center of the country, especially Paris,

held the key to national renewal; it was the hub around

which revived greatness must revolve.5

Unamuno focused on Castile

and Madrid as the center from which national regeneration

would come. Another '98 exponent of this view was the Valencian

author José Martínez Ruiz, known as "Azorín."

For him, the most important cultural currents in the Spanish

revival were the Generation of '98, Wagnerism, and landscape

painting, which captured the essence not only of the distincitive

Spanish (largely Castilian) countryside, its mountains,

plains, rivers, light, and air, but also of the "soul' of

the country and its people, which was inseparable from the

earth they inhabited. Azorín and Unamuno promoted

Castile as the region in which the pure and authentic spirit

of the country resided.

Azorín was one of the

leading polemicists in search of the national quintessence,

and he wrote numerous articles that appeared in the periodicals

Diario de Barcelona and La vanguardia

on the subject of Castile and national identity. Certainly

Granados read these and internalized their message.6

It is ironic that Granados,

Azorín, Unamuno, and other proponents of Castilianism

were not themselves from Castile. Nonetheless, they and

likeminded spirits "defined the nation in terms of Castile,

the 'mother lode' of Spain from which the modern Spanish

State was to emerge: its spiritual core, center of past

imperial glories, and cultural home of renowned classical

poets, painters, and statesmen."7

It was, as Azorín put it, "that most glorious part

of Spain to which we owe our soul."8

The role music played in this

reinvention of national identity is central to understanding

the significance of Granados and Goyescas. For

his nostalgic attraction to Castile and Madrid ca. 1800

would find expression in a musical language that was thoroughly

modern and thoroughly Spanish, European and casticista

at the same time, thus bridging the gap between liberal

and conservative even as Unamuno had prescribed.

Granados's attraction to the

life and art of Francisco Goya y Lucientes (1746-1828) in

particular came to flower at a time when Spain was searching

its past for great figures, especially in painting, who

(it was thought) had delved so deeply into the Spanish "soul'

that they had found something of universal appeal.9

In this quest for past greatness, Goya most captured the

imagination of writers and musicians ca. 1900. The sesquicentenary

of Goya's birth in 1896 was the stimulus for a revival of

interest in the artist's depictions of Spanish life, its

history, customs, and personalities. In part, the disaster

of 1898 seemed reminiscent of that of 1808, when Napoleon

invaded Spain, and people now looked to Goya as a symbol

of Spanish resilience in the face of defeat.10

IIn particular, the bohemian

character of the majo and maja captivated

Goya and his admirers, and dominated the highly romanticized

image of old Madrid embraced by Granados and his contemporaries,

a fascination known as majismo. The real-life majo

cut a dashing figure, with his large wig, lace-trimmed

cape, velvet vest, silk stockings, hat, and sash in which

he carried a knife.11

The maja, his female counterpoint, was brazen and

streetwise. She worked at lower-class jobs, as a servant,

perhaps, or a vendor.12

She also carried a knife, hidden under her skirt.

Although in Goya's day the

Ilustrados (upper-class adherents of the Enlightenment)

looked down their noses at majismo , lower-class

taste in fashion and pastimes became all the rage in the

circles of the nobility, who were otherwise bored with the

formalities and routine of court life. Many members of the

upper class sought to emulate the dress and mannerisms of

the free-spirited majos and majas . Among

the most famous epigone of the majas was the XIIIth

Duchess of Alba, María Teresa Cayetana (1776-1802),

who was the subject of several paintings and drawings by

Goya.

With the renaissance of majismo

ca. 1900, authors and writers focused on the majo/a

as an embodiment of casticismo. Vicente Blasco

Ibáñez wrote a novel entitled La maja

desnuda (1906), while Blanca de los Rios de Lamperez

contributed Madrid Goyesco (Novelas) (1908). In

1909, Zacharia Astruc wrote a series of five sonnets inspired

by Goya's La maja desnuda, entitled La femme

couchée de Goya. The following year, Francisco

Villaspesa presented his verse-play La maja de Goya.

The composer Emilio Serrano collaborated with Carlos Fernández

Shaw on an opera entitled La Maja de Rumbo (The

Magnificent Maja), which premiered in Buenos Aires in 1910.13

It became fashionable as well to reproduce Goya's

paintings as tableaux vivants. One such event in

Madrid in 1900 simulated four of the master's works as a

benefit for the needy and was attended by the royal family

and other nobility.14

Not only

the paintings and cartoons of Goya influenced Granados,

but also the writings of Ramón de la Cruz (1731-94),

the leader of literary majismo during Goya's lifetime.

His over 400 one-act comedies, or sainetes, portray

in delightful detail everyday life in the Madrid of that

epoch.15

His stage works were highlighted by the music of Blas de

Laserna (1751-1816) and Pablo Esteve (b. ca. 1730). Laserna,

director of the Teatro de la Cruz, composed about a hundred

sainetes, as well as zarzuelas and incidental music.

As José Ortega y Gasset pointed out about Cruz and

his collaborators, "his famous sainetes are, literally,

little more than nothing, and what is more, they did

not pretend to be poetic works of quality" [emphasis

added].16

Both Goya and Cruz, then, served

as models for composers around 1900 seeking to infuse their

stage works with the spirit of majismo. Francisco

Barbieri's zarzuela Pan y toros (Bread and Bulls)

of 1864 had been a big hit and was just the beginning of

a major eruption of musical theater replete with majos

and majas (see table 1).

Table 1: Musico-Theatrical

Works Inspired by Majismo, 1873-192017

| Title |

Type |

Author |

Year |

| La gallina ciega |

zarzuela |

Caballero/Carrión |

1873 |

| Las majas |

opera |

Mateo/unknown |

1889 |

| Majos y estudiantes, o el rosario de la Aurora |

sainete |

López Juarranz/Montesinos López |

1892 |

| San Antonio de la Florida |

zarzuela |

Albéniz/Sierra |

1894 |

| La maja |

zarzuela |

Nieto/Perrin Vico & Palacios |

1895 |

| La maja de Goya |

zarzuela |

Navarro Tadeo/Falcón Segura de Mateo |

1908 |

| Los majos de plante |

sainete |

Chapí/Dicenta & Repide y Gallego |

1908 |

| La maja desnuda |

sainete |

López Torregrosa/Custodio Fernández-Pintado |

1909 |

| La maja de rumbo |

opera |

Serrano/Fernández Shaw |

1910 |

| La maja de los claveles |

sainete |

Lleo/González del Castillo & Jover |

1912 |

| La maja de los madriles |

humorada |

Calleja/Plañiol Bonels & Fernández Lepina |

1915 |

| La maja del Rastro |

sainete |

Aroca/Enderiz Olaverri & Gómez |

1917 |

| San Antonio de la Florida |

comedia lírica |

Lleo/González Pastor |

1919 |

| La maja de los lunares |

opereta |

Obradors/Giralt Bullich& Capdevila Villalonga |

1920 |

| La maja celosa |

zarzuela |

Aroca/Gómez |

unknown |

Albéniz's zarzuela San Antonio

de la Florida made a deep impression on the young

Granados at its 1894 Madrid premiere, and it may have provided

the impetus for Granados's own majo -inspired zarzuela,

Los Ovillejos , only three years later. This zarzuela,

however, was never completed or produced. However, this

was merely the earliest predecessor to several other essays

in majismo by Granados (table 2). The most important

of these is the Goyescas suite for solo piano.

Table 2: Goya-esque Works by Enrique Granados

(b.1867; d. 1916)

Solo Voice and Piano

(available in Integral de l'obra per a veu i piano .

Ed. Manuel García Morante. Barcelona: Tritó,

1996):

Día y noche

Diego ronda, n.d.

Tonadillas (en estilo

antiguo). 1. Amor y odio, 2. Callejeo, 3. El majo discreto,

4. El majo olvidado, 5. El majo tímido, 6. El mirar

de la maja, 7. El tralalá y el punteado, 8. La maja

de Goya, 9-11. La maja dolorosa (Nos.1-3), 12. Las currutacas

modestas. Text F. Periquet. Prem. June 10, 1914, Palau de

la Música Catalana, Barcelona.

Stage

:

Ovillejos, ó

La gallina ciega (Sainete lírico). Zarzuela

in 2 acts, 1897, inc. Lib. José Feliu y Codina.

Goyesca: Literas y calesas,

o Los majos enamorados. Opera in 1 act. Lib. F. Periquet.

Prem. January 28, 1916, Metropolitan Opera, New York.

Piano (available in Integral

para piano de Enrique Granados . Ed. Alicia de Larrocha

and Douglas Riva. Barcelona: Editorial Boileau, 2002):

Crepúsculo (Goyescas) , n.d.

Jácara (Danza para

cantar y bailar), n.d.

Goyescas (Los majos enamorados)

(Goyescas: The Majos in Love). Book I: 1. Los requiebros

(The Flirtations), 2. Coloquio en la reja (Dialogue through

the Grill), 3. El fandango de candil (Fandango by Candlelight),

4. Quejas, ó La maja y el ruiseñor (Complaints,

or The Maja and the Nightingale). Prem. March 11, 1911,

Palau de la Música Catalana, Barcelona. Book II:

5. El amor y la muerte (Balada) (Love and Death: Ballad),

6. Epílogo (Serenata del espectro) (Epilogue: The

Ghost's Serenade). Prem. April 2, 1914, Salle Pleyel, Paris.

El pelele (Escena goyesca).

Prem. March 29, 1914, Terassa, Spain.

Reverie-Improvisation.

Recorded at Aeolian Company, New York, 1916.

The purpose of this paper is

not to present a complete analysis or even summary of the

music of Goyescas, a work of great subtlety and

sophistication. Suffice it to say here that the elements

that connect it to Goya are the following:

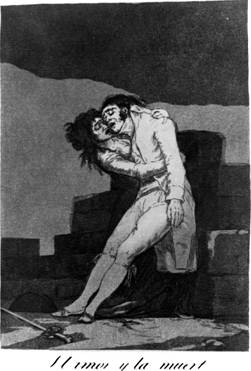

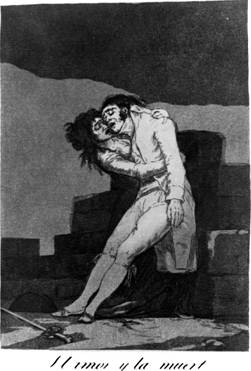

• Two movements,

"Los requiebros" and "El amor y la muerte," are inspired

by Goya's etchings Tal para cual (ill. 1) and

El amor y la muerte (ill. 2) in the Caprichos

.

Ill. 1: Tal para cual (Two of a Kind), from Goya's Caprichos

Ill. 2: El amor y la muerte (Love and Death), from Goya's Caprichos

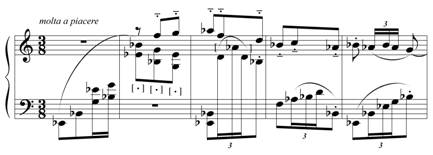

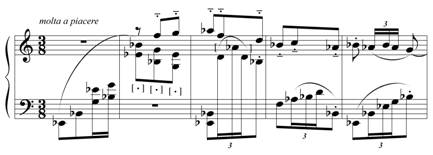

• The opening movement

is based on a tonadilla by Blas de Laserna entitled

"Tirana del Trípili" (ex. 1).

Ex. 1: Opening, "Los requiebros," a "copla" quoting the tonadilla "Tirana del Trípili" by Blas de Laserna (1751-1816)

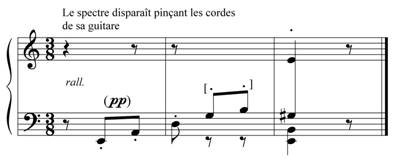

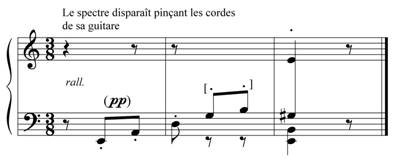

• There are abundant

references to the popular culture of Goya's Madrid, including

intimations of guitar rasgueo and punteo

(strumming and plucking) (ex. 2), formal plans based on

the alternation of coplas and estribillo

(verse and refrain), as well as a movement evoking the custom

of dancing the fandango by the light of a candle,

which had served as the basis for a popular sainete

by Ramón de la Cruz (ex. 3).

Ex. 2: Conclusion of "Epílogo," imitating guitar punteo on the open strings

Ex. 3: Opening, "El fandango de candil"

In more general terms, Granados's

fixation on the rich visual detail of Goya's paintings results

in a music of surpassing sensuality, through melodic lines

encrusted with jewel-like ornaments and harmonies studded

with added tones, like thick daubs of impasto applied to

the canvas with a palette knife. Intricacies in rhythm,

texture, and harmony even suggest the tracery of latticework

and lace. And, in fact, the chromaticism, ornamentation,

and sequencing in Goyescas harken back to the

rococo style that prevailed for so long in Spain, and particularly

to Scarlatti,18

several of whose Sonatas Granados arranged for piano.

After performing Goyescas

in Paris in 1914, Granados shed light on the nature

of his Goya-esque inspiration in an interview with the Société

Internationale de Musique. For Granados, "Goya is the representative

genius of Spain," and he himself was deeply moved by Goya's

statue in the vestibule of the Prado. It inspired him to

emulate Goya's example by contributing to the "grandeur

of our country. Goya's greatest works immortalize and exalt

our national life. I subordinate my inspiration to that

of the man who has so perfectly conveyed the characteristic

actions and history of the Spanish people." 19

Granados's patriotic fervor

was no doubt rooted in his family's history of military

service, but it also has to be understood in the post-1898

context. Granados is clearly trying to define Spanishness

by tapping not only into the psychology of Goya but, in

his view, the underlying psyche of the whole nation of Spain.

Like Unamuno and Azorín, Granados considered Castile

to be the heart and soul of Spain itself, and Goyescas

encapsulated his feelings and attitudes about the

nation and its identity.

The Parisian press and public

were ecstatic over these latest jewels of Spanish musical

art. Commentators were quick to seize on whatever evidence

the works presented of the Spanish essence and soul. One

anonymous critic expatiated on the importance of Granados's

Castilian orientation with a breathtakingly pithy overview

of regional aesthetics:

Asturias, Galicia, the Basque country,

and Catalonia exhibit different aesthetic currents, coming

generally from outside Spain; Andalusia, Murcia, and Valencia

are impregnated with the Hispano-Moorish tradition; only

the heart of Spain, Castile and Aragon, are free of any

foreign intervention. It is that Spain that has produced

the art of Granados; it is that national spirit, in all

its purity and integrity, which animates his work and gives

it that inimitable color, that special color.20

Of course, this was not true, as the interior

of the country had been overrun and occupied by various

invaders over the centuries, including Moors and the French.

The influence of Italian culture had been immense in the

eighteenth century.21

But despite historical realities, these notions enjoyed

enormous currency at the time, and few critics seem to have

questioned them seriously. Spaniards themselves left no

doubt about Granados's status: "He is the singer of the

spirit of our race, and the voice of our land," exclaimed

the pianist and critic Montorio-Tarrés.22

These fevered attempts

to affirm racial, ethnic, and national identity were driven,

in part, by a Darwinian conviction that modern Europe was

in the grips of creeping decadence through a dilution of

racial heritage. The general fear was that "the European

peoples, descendants of a lengthy evolution, were threatened

by an inevitable decrepitude and condemned to an approaching

demise by the rise of more barbaric and vigorous peoples."

23

One way to stem this tide was through an equally vigorous

reaffirmation of cultural identity and racial roots, particularly

in music. Regression to the pure ethnicity of the nation's

or region's origins was seen as a precondition for national

renascence.24

This accounts for the "preoccupation with popular culture

and is inseparable from a faith in native virility and morality,

which contrast with the corruption of foreign influence

and cosmopolitan decadence."25

For many listeners at the time,

in his Goyescas Granados had captured the elusive

"essence" of Spain, for which critics and aestheticians

were always on the lookout. Divorced from mere historical

events and facts, this essence was immutable and perenniel.

"Eternal truths of eternal essence" were, Unamuno wrote

in En torno al casticismo, independent of history,

even as the immortal soul was independent of the vicissitudes

of corporeal existence.26

In such a statement one detects strains of both

perennialism and primordialism, evocations of a long and

distinguished national history, rooted in a racial essence

that was immutable.27These

two historical paradigms inform much of the critical reception

of Goyescas.

Thus, a contemporary journalist

was moved to note that "No one has made me feel the musical

soul of Spain like Granados. [Goyescas is] like

a mixture of the three arts of painting, music, and poetry,

confronting the same model: Spain, the eternal 'maja.'"28

The arts as well as the nation itself were unified in the

image of the maja, had taken the place of the Virgin

Mary as the appropriate icon for modern Spain. Granados

had captured precisely this in his music, which led Luis

Villalba to a flight of poetic fancy that nonetheless encapsulates

a profoundly nationalistic sentiment:

And above the fabric of melodies

and harmonies floats a supplication, like a very pure song,

in which the sexuality of the fiesta and the love of color

with music unite with the black eyes of the Maja-Nation,

of the priests in black in darkened side streets, and of

secret tribunals and autos de fe in plazas shaded

by convents, and of Holy Week processions and convulsive

insane asylums and nocturnal witches.

Villalba summons up a whole

assortment of images from Goya's paintings here to make

his point: Goya and now Goyescas captured the

national essence, in both time and place, like nothing else.29

In concluding, one hastens

to point out that Granados expressed disdain for politics

and felt it beneath an artist to become enmeshed in political

controversy. But regardless of his own motivation in composing

the work, Goyescas is one of the most significant

political statements in Spanish music of that era, for it

proclaimed the centrality of Castile—not Catalonia or Andalusia—to

Spanish national identity and deployed Goya and the majo

as icons of Castile's preeminence. In so doing, Granados

rejected the separatist sentiments of his fellow Catalans

in favor of a united Spain under Castilian control, at a

time when regionalism was threatening to pull the country

apart. Moreover, Granados's aesthetic dovetailed with Unamuno's

vision of a Spain rooted in its own traditions but fully

incorporated into the mainstream of European civilization.

Almost a century later, this vision has proved prophetic.

1

Francisco Márquez Villanueva, "Literary Background

of Enrique Granados,' paper read at the "Granados and Goyescas" Symposium, Harvard University, January 23, 1982,

10.

2

Cited in ibid., 11.

3

Xose Aviñoa, La música i el modernisme

(Barcleona: Curial, 1985), 357.

4

Trans. and cited in Amy A. Oliver, "The Construction of

a Philosophy of History and Life in the Major Essays of

Miguel de Unamuno and Leopoldo Zea' (Ph.D. diss., University

of Massachusetts, 1987), 106. Unamuno turned away from Europeanization

after 189, a year of personal crisis that altered his philosophy.

Thereafter he promoted the idea of hispanidad,

the distinctive traits that united people of the Hispanic

world, in contradistinction to the rest of Europe, and that

resulted in their marginalization. This rejection of Europe

was accompanied by an increasingly interiorized spirituality.

5

Gayana Jurkevich, In Pursuit of the Natural Sign. Azorín

and the Poetics of Ekphrasis (London: Associated University

Presses, 1999), 42.

6

Azorín thought Granados's fellow Catalan Amadeu Vives

was the composer whose music most closely embodied the views

of the Generation of '98, though others would claim those

laurels for Granados himself. See José Martínez

Ruiz, Madrid, intro., notes, and biblio. José

Payá Bernabé (Madrid: Biblioteca Nueva, 1995),

174.

7

Jurkevich, In Pursuit of the Natural Sign, 32.

8

Ibid.

9

Generation of '98 literary criticism focused on the Siglo

de Oro, particularly Cervantes, Calderón, and

Lope de Vega. See Francisco Florit Durán, "La recepción

de la literatura del Siglo de Oro en algunos ensayos del

98," in La independencia de las últimas colonias

españolas y su impacto nacional e internacional,

ed. José María Ruano de la Haza, series: Ottawa

Hispanic Studies 24 (Ottawa: Dovehouse Editions, 2001):

279-96.

10

Ibid., 2.

11

Miguel Salvador, "The Piano Suite Goyescas by

Enrique Granados: An Analytical Study" (DMA essay, University

of Miami, 1988), 11.

12

Deborah J. Douglas-Brown, 'Nationalism in the Song Sets

of Manuel de Falla and Enrique Granados" (DMA document,

University of Alabama, Tuscaloosa, 1993), 75. See also Janis

A. Tomlinson, Francisco Goya: The Tapestry Cartoons

and Early Career at the Court of Madrid (Cambridge:

Cambridge University Press, 1989), 32.

13

A tonadilla with this same title with music by

José Palomino premiered at the Teatro Príncipe

in 1774.

14

See Nigel Glendinning, Goya and His Critics (New

Haven: Yale University Press, 1977), 19. The event was reviewed

in Blanco y negro on April 7.

15

The word sainete comes from saín ,

fatty parts of a kill given to hunting dogs. Thus, sainete

means literally a kind of treat or delicacy (in cooking,

it means seasoning or sauce).

16

José Ortega y Gasset, Papeles sobre Velázquez

y Goya, 2d ed., rev., ed. Paulino Garagorri (Madrid:

Alianza Editorial, 1987), 300.

17

Derived from Luis Iglesias de Souza, Teatro lírico

español, 4 vols. (Coruña: Excma. Diputación

Provincial de la Coruña, 1994).

18

Salvador, "Goyescas,' 47, finds the suggestion of acciacaturas,

a particular kind of dissonant ornament associated with

Scarlatti, in 'El fandango de candil," m. 105.

19

Jacques Pillois, "Un entretien avec Granados," S.I.M.

Revue musicale 10, suppl. 104 (1914): 3. "Goya est

le génie representatif de l'Espagne. Dans le vestibule

du musée du Prado, à Madrid, sa statue s'impose

au regard, la première. J'y vois un enseignement:

nous devons, à l'exemple de cette belle figure, tenter

de contribuer à la grandeur de notre pays. Les chefs-d'oeuvre

de Goya l'immortalisent en exaltant notre vie nationale.

Je subordonne mon inspiration à celle de l'homme

qui sut traduire aussi parfaitement les actes et les moments

caractéristiques du peuple d'Espagne."

20

Press reaction to the concert is summarized (in Catalan

translation) in "L'Enric Granados a París," Revista

musical catalana 11 (1914): 140-42. This quote is

from a review in Paris-Midi by Le Colleur d'Affiches.

"Asturies, Galicia, el país basc i Catalunya reben

corrents estètiques diferents, vingudes generalment

de l'exterior; Andalusía, Murcia i Valencia estàn

impregnades de tradicions hispano-moresques; solament el

cor d'Espanya, Castella i Aragó, viu sostreta de

tota intervenció estrangera. Es d'aquesta Espanya

que l'art d'en Granados ha sortit; es aquest esperit nacional,

en tota sa puresa i sa integritat, que anima la seva obra

i li dóna aquest color inimitable, aquest color especial."

21

See E. Inman Fox, "Spain as Castile: Nationalism and National

identity," in The Cambridge Companion to Modern Spanish

Culture, ed. David T. Gies (Cambridge: Cambridge University

Press, 1999), 29. The impact of Arabic on Castilian is one

obvious example of "foreign intervention."

22

"L'Enric Granados a París," in Excelsior

by E. Montoriol-Tarrés. "Es el cantaire de l'ànima

de la nostra raça, és la veu de la nostra

terra." Of the 1913 New York premiere of Goyescas

by Schelling, a reviewer for the New York Times

thought the work gave evidence of Granados's individuality,

and that the Spain "embodied in his music is authentic."

Authentic compared to what? Evidently to Albéniz,

who "saw Spain through the veil of the modern Frenchman."

Given the immense influence of Schumann, Liszt, and Chopin

on Granados's late-Romantic idiom, was his españolismo

necessarily more "authentic" than Albéniz's?

In any case, these sentiments reflect those of Pedrell,

who also found French influence "corrupting."

23

Lily Litvak, España 1900: Modernismo, anarquismo

y find de siglo (Barcelona: Anthoropos, 1990), 246.

24

One is reminded of Christopher Hitchens's view of this sort

of thing: "The unspooling of the skein of the genome has

effectively abolished racism and creationism. . . . But

how much more addictive is the familiar old garbage about

tribe and nation and faith." See Letters to a Young

Contrarian (Cambridge, MA: Basic Books, 2001), 108.

25

E. Inman Fox, La invención de España (Madrid:

Catedra, 1997), 16.

26

Frances Wyers, Miguel de Unamuno: The Contrary Self

(London: Tamesis Books, 1976), 3.

27

See Anthony D. Smith, Nationalism: Theory, Ideology,

History (Cambridge: Polity Press, 2001), 49-51.

28

Gabriel Alomar, "Las Goyescas," El poble català,

September 25, 1910. "Nadie como el me ha hecho sentir el

alma musical de España," declared Gabriel Alomar.

"[ Goyescas es] como una mezcla de las tres artes,

pintura, música, poesía, delante de un mismo

modelo: España, la 'Maja' eterna."

29

Luis Villalba, Enrique Granados: Semblanza y biografía

(Madrid: Imprenta Helénica, 1917), 33. "Y sobre

el tejido de melodias y armonias, flota una súplica

como de canción bien castiza, donde á la sexualidad

en fiesta y á los amores del color con la música,

se junta la negrura de ojos de la Maja-Nación, negrura

de clérigos en callejuelas sin sol, y de tribunals

secretos, y autos de fe en plazas sombreadas por conventos,

y procesiones de Semana Santa y manicomios convulsivos y

brujas nocturnas." |