Some Aspects of the Tonadilla escénica in Its Late Phase

Elisabeth Le Guin

Repaso

The term tonadilla can

refer to several different musical genres, depending on

the period in question. In the second half of the eighteenth

century the term is properly tonadilla escénica,

and it means a kind of comic intermezzo in Spanish: a brief

work for one, two, or sometimes more singers and a small

theater orchestra, sung more or less throughout, and expressly

created to be staged between the acts of longer works like

operas, zarzuelas, or spoken plays. The genre was place-specific—the

great majority of tonadillas escénicas

were written in and for Madrid—and period-specific as well.

The generally accepted date for the first work answering

to this description is 1757, and although tonadillas

were occasionally written well into the nineteenth

century (Francisco Barbieri wrote one in 1881), the genre

had ceased to be a vital tradition by about 1810.

There was a great deal of tension

during the second half of the eighteenth century between

the afrancesados, those Spaniards who followed

the lead of the French in matters of philosophy, the arts,

and fashion, and those who, for a variety of reasons, cleaved

fiercely to old (or sometimes re-invented) Spanish traditions.

This is reflected in the tonadilla texts, which

are topical, directly treating current events, fashions,

and the foibles of audience members, often in terms of their

nationalized affiliations; at the same time, the musical

language cooks up a unique mix of autochthonous Spanish

dance types, French sentimentality, and the lively, limber,

declamatory Neapolitan comic style.

The madrileños

ate it up. Tonadillas enjoyed a tremendous vogue

in Madrid. By the 1780s, the company at each of the two

main theaters was presenting sixty to seventy new works

every season; thus, during the season, a new tonadilla

could be seen in Madrid every few days. The archival

legacy of this time is impressive: the Biblioteca Municipal

de Madrid has almost 2000 tonadillas in manuscript,

as well as 536 sainetes of the great satirical

observer of Spanish customs, Ramón de la Cruz, about

a 100 of which have substantial written musical interludes.

This veritable ocean has been astonishingly little navigated.

Very few tonadillas have been published. La

muerte y resurección de la tirana of Blas de

Laserna, from which comes the "Tirana del Trípili"

used by Granados for "Los requiebros" in his Goyescas,

is very much the exception. Furthermore, the collections

have never been systematically catalogued, although the

MSS are well preserved and lovingly cared for.

Only the great Spanish

musicologist José Subirá can be said to have

really known this repertory; he achieved this by making

the tonadillas central to his life's work, in

the process eschewing academia, teaching, society, and most

visible means of financial support. Since his magnificent

three-volume study of 1932,1

and until the last couple of years, in which scholars at

the Universidad Autónoma de Madrid have produced

an important article and a fine exhibition catalog, which

includes a collection of essays, there has been precious

little scholarly work of any kind on the genre.2

To this day, virtually none of it is in English.

Madrid 's Centro Conde Duque,

which houses the Biblioteca Municipal, has sponsored a series

of tonadilla concerts over the last few years,

in which the madrileños can enjoy the pieces

that their ancestors raved about. In coordination with these

efforts, a good recording has only recently been released;

it is the first adequate performance of any of these works

on disc.3

Justificación

Fine though the concerts are

and the recording is, I cannot imagine that the tonadilla

escénica will ever recuperate the popularity

it once had with its listening public. It was too much a

phenomenon of its time; we have lost too much of the original

context. Thus, the genre embodies one of the fundamental

paradoxes of the discipline of musicology: what use can

there be in poring over the fossilized remains of an art

form whose immediacy was its soul and reason for being?

This question hovers poignantly

over my recent work in the genre. If pressed for an answer,

I would have to say that the use of such study is in looking

more closely at, and thus honoring, the past; and that doing

this is important because we tend to find that in honoring

the past, we better come to understand ourselves in the

present. Tonadillas escénicas provide windows,

some of astonishing clarity and others of fascinating distortion,

onto a place and a time that have disappeared forever—and

which yet persist, in a thousand likenesses large and small.

To name only a few of the largest: Spain in the period 1785-1805

and Spain in 2005 are both contending with the impact of

a big wave of immigration; both are still emerging from

long periods of cultural isolation (the one from the long

Hapsburg dynasty, the other from the dictadura

of Franco) into relative modernity; both are prosperous

for the first time in living memory. Questions that arise

in relation to the one period tend to apply to the other,

a fascinating and perilous exercise in historical relativism.

Thus, an immediacy—a mediated immediacy, I suppose we would

have to call it—does in the end emerge.

Or, to answer the question

in another way (but perhaps, in the end, a more appropriate

one): there is the fact that the madrileños

still chuckle at the humor in these works.

Ejemplo

I propose to concentrate here

on a single tonadilla. I will not attempt to be

particularly synoptic nor systematic about my treatment.

Those who are interested in the general textual, structural

and stylistic features of the genre cannot do better than

to go to Subirá, who describes them with mastery;

and those who would like to get to know the piece more thoroughly

can find this particular tonadilla in a good recent

edition. Rather, I hope here to give a brief glimpse of

how these works once operated, and of what can still be

interesting and attractive in them.

The work is entitled La

lección de música y de volero, and its

music was composed by Blas de Laserna (1751-1816). In all

likelihood, so was its poetry. Laserna, a remarkable jack-of-all-trades

and one of the most prolific composers in the whole eighteenth

century, wrote the libretos for a number of his

more than 800 (!) tonadillas . The first performance

came in the spring of 1803. From the worn and much-marked

condition of the parts, it appears to have been a particularly

popular work, probably re-staged a number of times during

ensuing years.

|

Mutacion

de sala di ensayo con puerta en el foro q.e figure

la entrada de la calle sillas &a.

The work opens with "Berteli" and

"Eusebio," tenor and bajo respectively. Berteli

plays the part of the "autor," or company director.

The two are trying to figure out how

they will mount the coming summer season of tonadillas,

without any women singers to speak of.

After this opening number, we get

a spoken exchange in which Eusebio offers to sing

the women's parts, and Berteli agrees to let him

do it.

Then some women do appear: la Virg

(=María Josefa Virg), and "la Bolera," a

bailarina .

There is some banter between the

men and these women. They still do not know what

tonadilla to put on, because they still lack a dama

de parte de cantado . . . .

. . . so they decide to pass the

time as fruitfully as they can until she shows up:

to wit, Eusebio engages to practice solfa

with La Virg.

Meanwhile, Berteli tells the bailarina

, "While they have their lesson, I'll review

the bien parado you taught me yesterday." |

|

A

rehearsal hall with a door in the back through which

can be seen the entry to the street; seats etc.

Allegro, A Minor, 2/4 time

The singers' real names were Sebastiano

Berteli and Eusebio Fernández. It was common

practice for tonadilleros / as

to act and sing under their own names. De la Cruz

used the same, curiously "transparent" convention

in his sainetes .

This, like most of the meta-theatrical references

with which tonadillas abound, is documentary.

Due to repeated administrative conflicts and failures

from 1799-1802, the Madrid theatrical companies

were still in a woeful state. 4

There is a fair amount of this

sort of gender silliness in the tonadillas ,

up to and including having a bajo sing an entire

sentimental aria in falsetto, or a soprano an entire

aria in the buffo tenor range (an example occurs

in Laserna's Cómica y la operista

of 1783).

The bolero was at the height of its popularity

at this time, and boleros, along with fandangos

, contradanzas , padedús

, and minués , were often programmed

as independent events alongside operas and tragedies.

From the 1790s, theatrical companies had begun keeping

dancers on staff for this.

The tonadilla had always

been a genre heavily reliant on the singing and

dancing of women. 5By

this late date in the history of the genre, the

level and nature of that singing and dancing had

evolved to require professional operatic and dance

techniques. Gone were the days of the untrained

comic singer-actress-dancer.

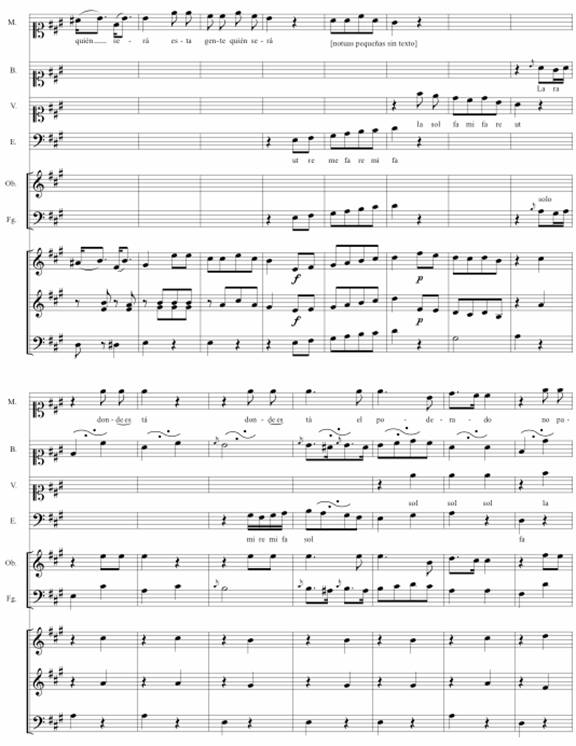

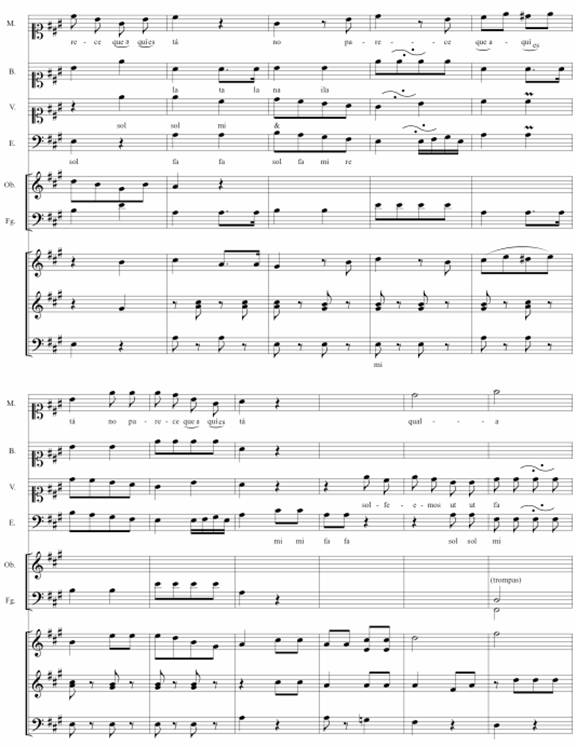

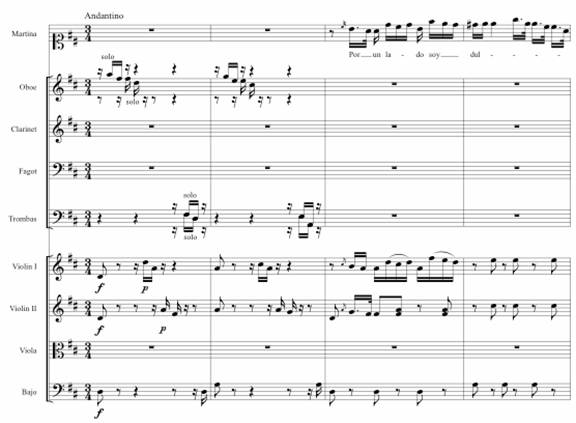

Andantino, A Major, 3/4, movimiento

de seguidillas (=bolero).

María Josefa Virg did not

specialize in singing parts (she was to achieve

her greatest fame in 1806 as Paquita in Moratín's

enormously popular El sí de las niñas

).

This refers to the practice whereby

at the end of a bolero —or even at the

end of sections or phrases—the dancers froze, holding

elegant and artful poses, competing for cries of

"Bien parado!" from the onlookers. 6

There is a sardonic twist here,

made clear in later spoken passages. Berteli (as

his name suggests) was of Italian birth, and the

very idea of an Italian trying to dance the bolero

was evidently funny to the audience. |

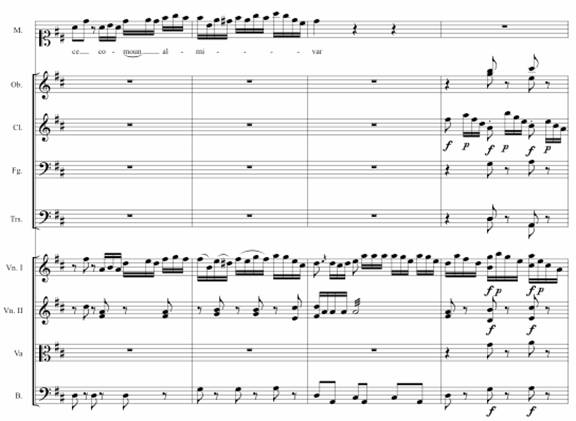

The orchestra is the minimum

for tonadillas: two violins (doubled in this production,

as there are two surviving parts for each) and contrabajo,

usually doubled by guitar and/or keyboard.

This is a different solfa

system than the one most of us know. Possibly it is

deliberately wrong, a parody; but it is perfectly consistent

with itself, to an extent that suggests instead that it

is a distinct, apparently tetrachordal system.

One can see that Eusebio must

have been a pretty agile bajo. In the theater records

he is described with the Italian term buffo (as

well as gracioso, the old term for a comic character).

A good measure of his vocal and dramatic skill can be found

in the fact that in May and June of 1802, about a year before

this tonadilla premiered, he sang the title role

when Mozart's El casamiento de Fígaro

(in Castilian translation) was first staged in Madrid at

the Teatro de los Caños del Peral.

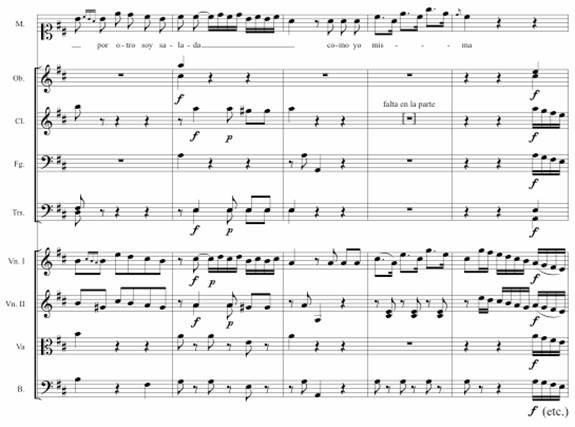

At bar 5,

Berteli begins his own melody (and, we presume, his attempts

at imitating La Bolera's dance) with a series of vocables.

It is interesting to take note of the differences between

the "neutral" (=Italian comic) style of the music sung by

Eusebio and la Virg, and what Berteli sings (the dotted

rhythms, the relatively measured delivery, the tied-over

phrase-ending characteristic of seguidillas and

boleros). After sixteen bars of this artful group

chaos, however, the musical landscape changes rather abruptly,

with the entrance of a much larger orchestra—viola, clarinet,

oboes, bassoon, and horns. The meter, the tempo, and the

tonality, however, do not change, although we lose the bolero

"feel," by virtue of losing the characteristic dotted rhythms

and the tendency toward a harmonic rhythm that moves on

beats one and two of a three-beat bar.

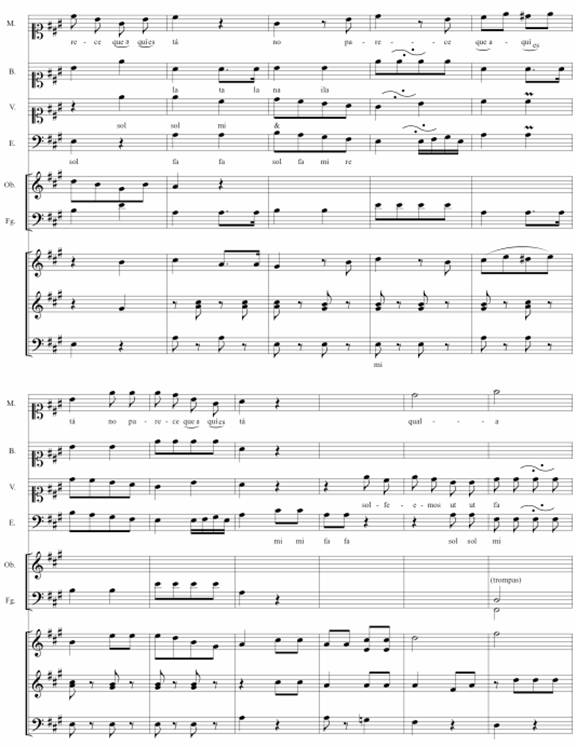

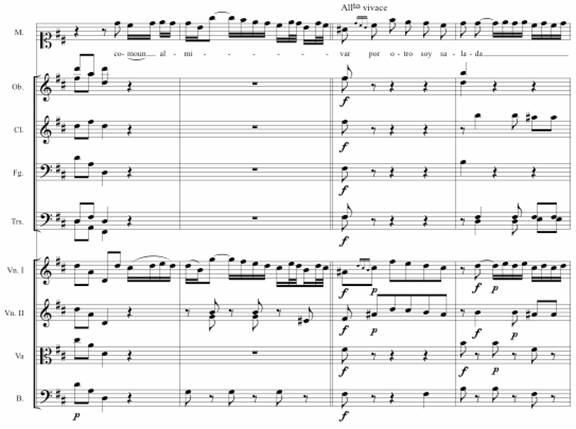

|

The

grand introduction is for the arrival of La Martina,

the long-awaited parte de cantado , and

the artist for whom this tonadilla served

as a formal introduction to the Madrid audience.

She enters singing a virtuoso aria

with a typically silly allegorical text, in perfect

disregard for the others, who (understandably) fall

silent.

We might imagine them striking

poses of surprise and interest at this unexpected

entry. |

|

This

tonadilla marks the first time Martina

Iriarte sang at the Teatro de la Cruz, where this

tonadilla was produced. 7

Although we do not have much detailed information

about La Martina, from the vocal writing it is clear

that she must have been well trained in the Italian,

bel canto style.

Stage directions of this or any

other type are almost entirely lacking in tonadillas

; we must usually infer them.

|

It is interesting to note that as soon as

La Martina sings, Laserna once again cuts back the orchestra

to its minimum. Whereas the augmented forces that introduced

her amounted to a kind of sonic topos—signifying

"opera," as opposed to "intermezzo"—the reduction here may

have been in order to show her vocal prowess to best advantage.

It was the custom in tonadillas for the violins

to double the voice lines, and quite rare for the texture

to operate otherwise. The fact that La Martina could sing

something this showy without that support is itself an advertisement

for her talents.

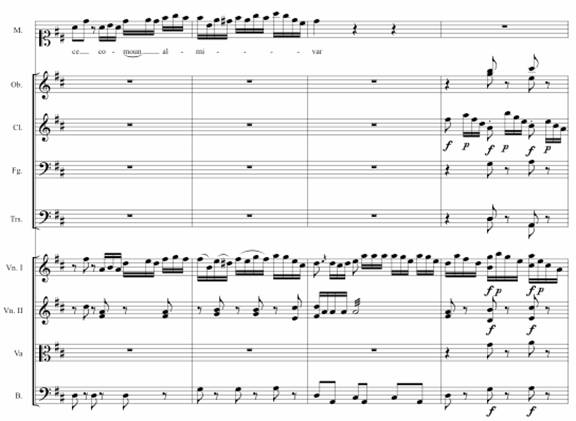

Martina seems unaware of the others at first,

absorbed in practicing her aria. We know she sees them,

however, when the meter and tempo change:

Now

everyone is, as it were, "on the same page" for

the first time. Each accordingly begins to "do their

thing," simultaneously: the standard signal for

an Italian comic finale, and indeed the music is

a die-cut Italianate Allegro.

• Martina complains,

diva-style, that the director of the company does

not appear.

• The solfa

lesson resumes.

• The bolero

lesson continues.

At bar 36 of the example ,

Martina begins to practice her aria again.

Berteli begins to sing along with her, introducing

her to the audience in buffo style, as

she shows off her cantabile .

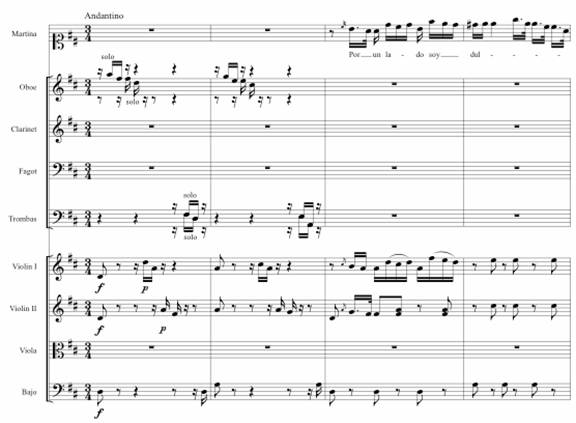

|

|

The apparent metrical contradiction here—a bolero

in an Allegro 2/4 time—is made possible by

a clever rhythmic sleight-of-hand on Laserna's part.

When Berteli enters in bar 19 of the example (doubled

this time by the bassoon), he sings his original bolero melody (ex. 1, bar 5 ),

its three beats now extended across three

bars of the ongoing 2/4 time. Thus through

a simple adaptation of harmonic rhythm, we get to

hear the dance that had come to represent quintessential

Spanishness, even to Spaniards themselves, without

ruffling the bustling Italianate surface. The moment

is a brilliant example of musical hibridación

.

At this point, the harmonic rhythm

reestablishes itself seamlessly in two-bar phrases;

the bolero lesson is over. From here to

the end of the number, there is that escalation

of energy and activity that we (just like audiences

of the day) know so well from Italian comic opera

finales, culminating in repeated, emphatic cadences.

|

There is quite a bit more

in this piece, which is on the long and elaborate side for

a tonadilla. The general gist is the introduction

of La Martina, who emerges as very diffident about her evident

skills, and very anxious to please: this was the ritual,

placating posture of the nueva before the notoriously

fickle and judgmental Madrid audiences, a posture documented

in literally hundreds of tonadillas.

I will focus on just one other

place in this piece, where again, dance music plays an interesting

role. This occurs when, having at last a dama de cantado,

the company members set about choosing their tonadilla.

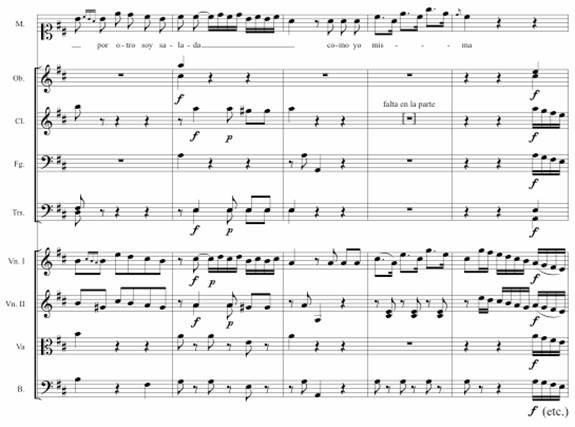

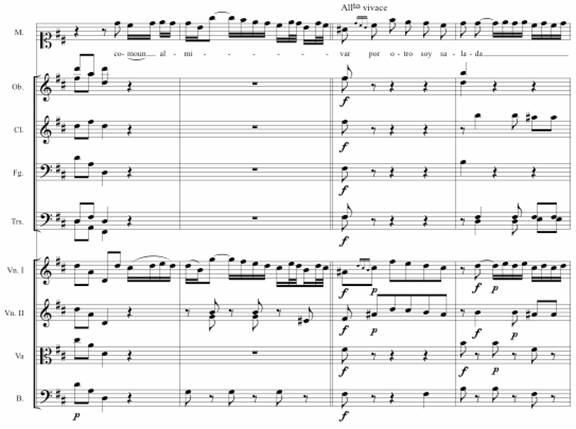

Berteli

asks Martina, "What kind of character do you like

[to play], serious or maja?"

She replies with a song:

On the one hand I'm sweet

as sugar syrup

On the other I'm salty

like myself.

I'm a compound,

of pleasant sour-sweetness,

of majo and serious. 8

|

|

"Serious"

seems here to have meant "operatic" (itself an interesting

equation); the music La Martina offers in proof

of her "seriousness" would more likely be called

"sentimental" nowadays.

"Maja," meanwhile, is arguably

the most loaded term of the entire late eighteenth

century in Spain. Through it we may infer a host

of qualities that existed along a continuum of resistance

to everything that opera represented: autochthonous

culture, membership in the lower social classes,

grace and humor ( sal ), fierce nationalist

pride, an emphatically embodied personal genuineness.

. . .

This begins as a sort of bel-canto-ized

seguidillas : sweet indeed. 9

However, in bar 10, the last time Martina sings

"almivar" (sugar syrup), the accompaniment "goes

salty" on her (a shift to the relative minor via

a "wrong note," A#, and the V/vi is heralds, and

an up-tempo shift); our sentimental opera heroine

is suddenly another girl, purely through change

of seguidilla -type (although this time

she retains her opera-orchestra accompaniment).

Iriarte, despite her Italian training

and vocal presentation, seems to have been Spanish-born:

a distinction that mattered to the audience. Here,

with Laserna's expert assistance, she abruptly presented

them with her maja credentials.

The subtlety and artfulness of

Laserna's use of topical associations within a single

dance-type to create character is comparable to

the subtlety and artfulness of Rameau or Mozart.

|

Conclusión

It is worth noting, in conclusion,

that having demonstrated her maja nature, La Martina

does not thereafter "revert" to it. She could not have done

so. In 1803, such a simplistic solution to the question

of musical Spanishness (a question symbolized in this little

work by its own metatheatrical consternation over how to

choose which tonadilla to sing) could no longer

"fly." In fact, the piece-within-a-piece is never chosen;

or rather, it is the piece itself, which casually ceases

to frame its story-within-a-story and becomes its own subject

matter.

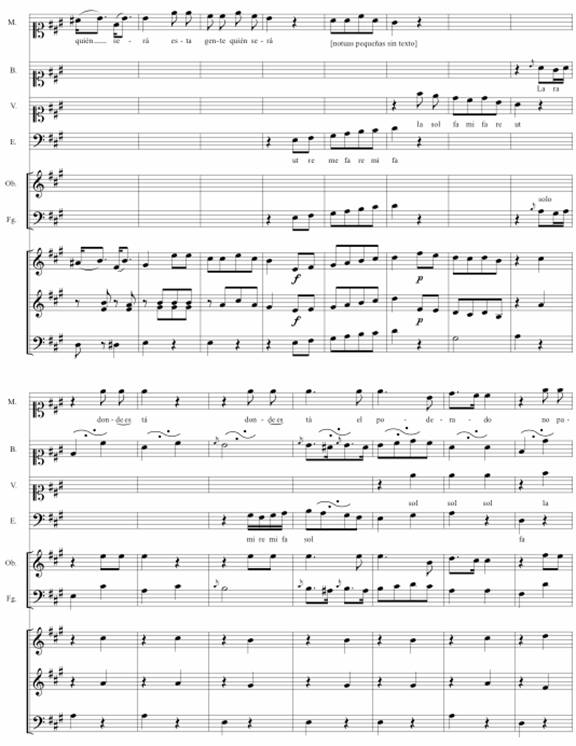

In the tonadilla's

middle section, or coplas , in a curious, hybrid

dance rhythm that might or might not be Iberian, the three

principal parts complain that things are not as they once

were in the realm of the tonadilla . In the second

verse, they sing as follows:

Martina

Ay, endless apasionados

for the Spanish style.

Berteli.

Well, then sing the tonadillas

of Morales and Misón.

Eusebio

Thus we'll have the grace

which the Nation has lost. |

|

Morales and

Misón we and still are generally celebrated

as the first composers in this genre; their works

date from the 1750s and 1760s respectively |

But of course, that grace

had already been lost forever—if indeed it had ever existed

in the ideal form yearned for here. If not everybody present

in the Teatro de la Cruz knew this yet, they would know

it soon enough, after the disastrous French invasion of

1808. In any case, Laserna clearly knew it already. Martina

sings:

I

don't know then, I don't know.

Ay, God what a thing.

What a thing, I don't know

in that case what we'll sing.

Ay, but joy anew

returns to give vigor to the soul,

the sweetness of calm

will always reign there. |

|

Allegro

Moderato, in common time and with majestic dotted

rhythms, after an abrupt but not wrenching move

to the key of Eb Major

With the second verse, Berteli

and Eusebio join in. Somehow, without benefit of

narrative transition, all the preceding doubt seems

to have evaporated. |

How is this "solution"

effected or justified? The answer is not evident in the

text at all, but it emerges quickly enough in the score:

to these serene words, La Martina begins an elaborate coloratura

in triplets, an exuberant display of thoroughly Italianate

virtuosity. The answer to the artists' collective dilemma

is thus announced clearly enough through musical style.

From this point to the end of the piece (and indeed from

this historical point to the effective end of the tonadilla

tradition), opera—"serious" music—had clearly won

the day.

1

José Subirá, La tonadilla escénica.

3 vols. (Madrid: Tipografía de Archivos Olózaga,

1928-30). Subirá himself published a useful shorter

"digest" version of his magnum opus: La tonadilla

escénica: sus obras y sus autores (Barcelona:

Editorial Labor, S.A., 1933).

2

See, for example, VV.AA., La Tonadilla Escénica:

Paisajes sonoros en el Madrid del S. XVIII (Madrid:

Museo de San Isidro, 2003) (exhibition catalog with chapters

by Begoña Lolo, Germán Labrador, Acensión

Aguerrí, Emilio Moreno, and others); and Lolo, Begoña,

"La tonadilla escénica, ese maldito género,"

Revista de musicología 15 (2002).

3

El maestro de baile y otras tonadillas (works

of Misón, Rosales, Esteve, Laserna and Moral), Ensemble

Elyma, dir. Gabriel Garrido, Harmonia Mundi, K617151, 2003.

4

See, for instance, Chapters 5-8 of Emilio Cotarelo y Morí,

Isidoro Maiquez y el teatro de su tiempo, Estudios

sobre la historia del arte escénico en España,

III (Madrid: Imprenta de José Perales y Martínez,

1902). Cotarelo's remarks are on p. 196.

5

"[L]as cantarinas embelesaban a los espectadores por las

gracias de los chascos o de los dichos propios de la plebe,

remedados con viveza y energía." ("The women singers

captivated the spectators with the grace of the tricks and

sayings of the common people, imitated with liveliness and

energy.") Memorial Literario de Madrid , September

1787. The entire text of this important early description

of the genre is given in Subirá, i, 285-87.

6

"[N]o todos tienen aquellos bienparados graciosos, en donde,

quedándose inmoviles, el cuerpo descubre con tranquilidad

y descanso hasta las más pequeñas gesticulaciones

del rostro. La serenidad en los pasos y mudanzas dificiles

es la primera cosa que se debe observar en este baile. .

. ." ("Not everyone has [can do] those attractive bien-parados,

in which, staying immobile, the body shows with calm and

repose even the smallest motions of the face. The serenity

in the steps and difficult moves is the first thing which

must be observed in this dance. . . .") Antonio Cairon,

Compendio de las principales regals del baile,

(Madrid 1820). Quoted in Javier Suárez Pajares, "Bolero,"

Diccionario de la música española e hispanoamericana

, ed. Emilio Casares Rodicio, with J. López-Calo

and I. Fernández de la Cuesta (Madrid: Sociedad General

de Autores y Editores, 1999- ).

7

Cotarelo asserts that the de la Cruz company was much the

weaker of the two at this time, being dedicated largely

to spoken drama. See Cotarelo, Isidoro Maiquez, 196.

8

Por un lado soy dulce / como un almibar; por otro soy salada

/ como yo misma; formo un compuesto / de un agridulce grato

/ de Majo y serio.

9

Here we should perhaps recall the truly chameleonic variety

of this dance type. Subirá suggests numerous sub-types

of seguidillas, in addition to the seguidillas

de bolero, which we have already encountered: seguidillas

aminuetadas, gitanas, de maja, de

gallego, etc. |