Apuntes Para Mis Obras

: Granados's Most Personal Manuscript and What It Reveals

Douglas Riva

The Pierpont Morgan Library in New York holds

a sketchbook by Enrique Granados (1867-1916), and it is

without doubt one of Granados's most intriguing manuscripts.

Apuntes para mis obras (Notes for My Works), the

title of the sketch book, contains sketches for the Tonadillas

and other works which, along with the piano suite

Goyescas and the opera of the same title, are united

by the common source of inspiration—the paintings of Francisco

Goya (1746-1828). Our understanding of Granados's genius

is greatly enhanced by studying this sketchbook.

Apuntes para mis obras is a black

leather-grained cloth-bound notebook, measuring 11.5 x 17

cm. In reality it consists of two separate notebooks that

are glued together and covered with one outer binding. The

first notebook consists of thirty-five pages, and the second,

of thirty-six pages of graph paper. Following the cover,

the first page of the manuscript states its title. The second

page bears a title for the musical sketches that fill the

first seventeen pages: Apuntes y temas para Ovillejos

(la gallina ciega ) [Notes and Themes for

Ovillejos (la gallina ciega )].

Granados did not place a date on any page of

Apuntes para mis obras. Since he said that he began

Ovillejos in 1900, we may assume that the sketches

relating to the opera were written around that time. The

Tonadillas, however, were not published until 1912.

Consequently, since Apuntes para mis obras contains

so many sketches for these songs, it is possible that he

continued to write in the notebook during the intervening

years.

For many years Apuntes para mis obras

was in the private library of the great Italian diva Amelita

Galli-Curci (1882-1963). Mme. Galli-Curci enjoyed an overwhelming

success in Barcelona during the 1913-1914 and 1914-1915

seasons, where she interpreted leading roles in Lucia

di Lammermoor, La Sonnambula, and Il Barbiere

di Siviglia, among other operas. Although it is not

known precisely how Apuntes para mis obras came

into her possession, it is not unreasonable to hypothesize

that Granados presented the sketchbook to Mme. Galli-Curci

in admiration for her art. However, it is also possible

that Granados's son Víctor either gave or sold the

manuscript to Mme. Galli-Curci during the period when both

were living in California, ca. 1960. Upon Mme.

Galli-Curci's death in November of 1963, Apuntes para

mis obras came into the possession of her close friend

William Seward of New York . Mr. Seward retained the manuscript

in his archive until it was acquired by the Pierpont Morgan

Library in 1985.

Granados's musical sketches in Apuntes

para mis obras include the sketches for Ovillejos-La

gallina ciega, and sketches for some of the Tonadillas

along with verses to be used as possible texts for

them. Curiously, none of his piano works are sketched in

the manuscript. Other material includes a paragraph describing

the composer's view of his Tonadillas and their

origins; pedagogical information; notes on orchestration;

drawings in the style of Goya of majas and majos

in pencil, ink and pastels; personal information (including

measurements for a standing screen and curtains and addresses)

and lists of works composed as well as projected works.

Some of the charming drawings are titled; others, including

a self-portrait, are not.

Granados began drawing early in his life. While

a student in Paris, 1887-1889, he sketched regularly with

his friend the painter Francesc Miralles (1848-1901). However,

for Granados sketching was not merely a student fancy but

an activity that he continued as a mature composer. In Apuntes

para mis obras Granados drew nine sketches of majas

and majos inspired by the art of Goya. Granados's

drawings show him to be a skilled amateur artist. There

are two drawings titled La maja de paseo (The

maja out for a walk), one executed in black ink and the

other in black ink colored with yellow, red, and green pastel

(figs. 1-2); two titled La maja en el balcón

(The maja on the balcony), one done in black ink and

the other in black ink, pencil and yellow and red pastel

(figs. 3-4; no. 3 also includes a self-portrait and La

maja dolorosa); and an untitled black ink drawing of

a majo (fig. 5). None of these drawings are related

to specific compositions by Granados. However, La maja

dolorosa (The sad maja), drawn in black ink,

could be related to the inspiration for the three Tonadillas

of the same title. Coloquio en la reja (Dialogue

through the grill), a drawing in black ink and pencil accented

with blue, yellow, and brown pastel (fig. 6), is also the

title of the second piece of the piano suite Goyescas.

Fig. 1: Granados, La maja de paseo

(The maja out for a walk)

Courtesy of Pierpont Morgan Library, New York

Fig. 2: Granados, La maja de paseo (The

maja out for a walk)

Courtesy of Pierpont Morgan Library, New York

Fig. 3: Granados, La maja dolorosa

(The sad maja),

self-portrait, and La maja en el balcón

(The maja on the balcony)

Courtesy of Pierpont Morgan Library, New York

Fig. 4: Granados, La maja en el balcón

(The maja on the balcony)

Courtesy of Pierpont Morgan Library, New York

Fig. 5: Granados, Majo

Courtesy of Pierpont Morgan Library, New York

Fig. 6: El coloquio en la reja (Dialogue

through the grill)

Courtesy of Pierpont Morgan Library, New York

Apuntes para mis obras contains one

page, which shows evidence that a drawing similarly executed

in black ink colored with brown pastel was removed from

the manuscript. Perhaps this drawing is one of a maja

(in the collection of Antonio Carreras Granados, grandson

of the composer).

As a piano teacher, Granados was highly successful.

Certainly he devoted a considerable portion of his life

to his students. It is not surprising, therefore, that Granados

included some of his pedagogical ideas in Apuntes para

mis obras. Many musicians and teachers will agree with

Granados's "Advice for Students" included in the manuscript

: "The most well-known works must be studied first."1

Granados also described some of the concepts for his piano

technique in the manuscript:

Technique is composed of strength, equality

and agility.

What contributes to strength?

Articulation.

The position of the body, arm and hand.

What contributes to equality [of the fingers]?

The balance of equal strength in all of the fingers.

What contributes to agility?

The suppression of all useless movement.2

Although Granados's introduction to the works

of Goya and his subsequent inspiration by Goya's art are

usually attributed to Fernando Periquet (1873-1940), librettist

for both the Tonadillas and the opera Goyescas,

Granados's first "goyesca" was in fact Ovillejos,

an opera with a libretto by José Feliu y Codina

(1845-1897). Its subtitle, La gallina ciega (Blind

Man's Bluff), is the same as the title of a famous Goya

painting. In an interview the composer stated that Ovillejos

was begun in 1900 and that he originally wrote El

fandango de candil, the third piece of the piano suite

Goyescas, for Ovillejos, but due to the

librettist's untimely death, the project was dropped.3

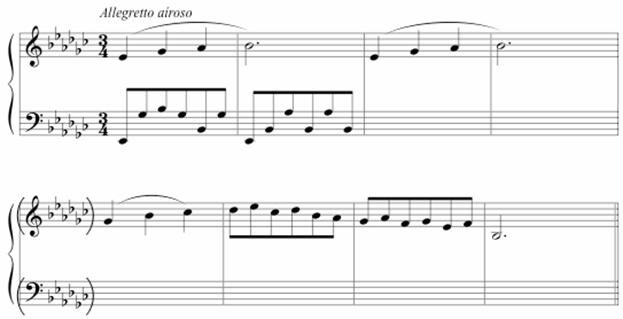

The first sketch for Ovillejos appears

on the second page of Apuntes para mis obras. The

character of the music would indicate that Granados intended

that music as an introduction or overture to the opera.

Since it is a sketch, the music is scored for piano and

not orchestrated. An excerpt from the sketch follows:

Ex. 1: Granados, excerpt from Ovillejos

The following pages include: 1) a scene scored

for chorus and piano, 2) fourteen measures of music scored

for piano labeled Introducción y intermedio,

and 3) other short sketches. Some of this material was later

expanded and orchestrated by Granados in a separate and

unpublished manuscript titled La gallina ciega,

now preserved in the Centre de Documentació Musical,

Barcelona.

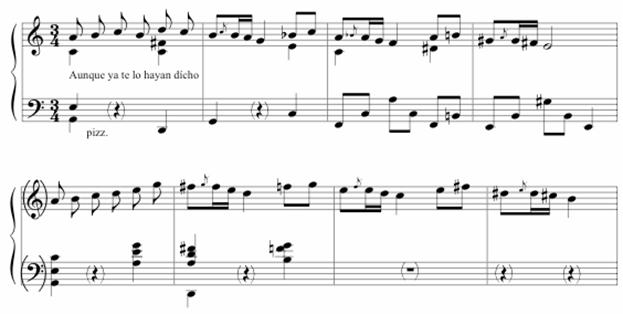

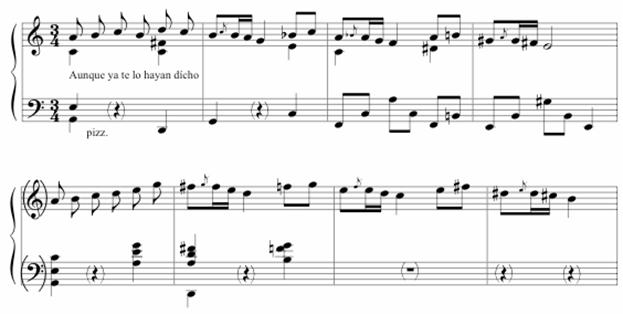

One of the most interesting aspects of the

material relating to Ovillejos found in Apuntes

para mis obras is the way in which Granados develops

an eight-measure sketch for piano with the text Aunque

ya te lo hayan dicho (Although they might have already

told you), presented as ex. 2. This example and all remaining

examples are complete as they appear in Apuntes para

mis obras.

Ex. 2: Granados, sketch for Ovillejos

The initial idea is expanded in ex. 3. Although

still scored for piano, in this sketch Granados now indicates

his ideas for possible future orchestration by these indications:

Cuerda, Ob. Fl. (strings, ob[oe], fl[ute]) and

Clar. (clar[inet]).

Ex. 3: Granados, sketch for Ovillejos

The first instrumentación

(orchestration) of this material, as labeled by Granados,

appears as ex. 4. Note that the melody is taken by the Oboe

and Corneta (cornet).

Ex. 4: Granados, sketch for Ovillejos

An alternate instrumentation for the music

appears as ex. 5. Notice how in this case Granados assigns

the melody to the Cello and Fagot (bassoon).

Ex. 5: Granados, sketch for Ovillejos

Apart from notating his orchestral sketches

in Apuntes para mis obras, Granados details some

of his ideas for the orchestration as follows:

An expressive melody with oboe and cornet

playing piano. Combining the strings, half playing

pizzicato, half bowed, against dotted notes in

the high register and with mute.

Motives of flute along with strings playing

with the mute.

Cornet playing noisily in the high register,

F, G, A-flat. With insistence.

Flute playing piano in the middle

register, combined with the bassoon in unison, 2 octaves

apart.

Clarinet doubling legato and piano

a motive with little movement, pizzicato

in the strings and harp.

Flute, lyre and strings in the high register.

Violins on the high strings along with the

soprano voice and sometimes doubled by a trumpet an octave

lower.4

Although a detailed comparison of Granados's

ideas for orchestration as notated in Apuntes para mis

obras with his completed orchestral works and operas

is beyond the scope of this paper, it would be interesting

to study how he might have realized these ideas in Ovillejos

and other operas such as Follet and María

del Carmen and in symphonic works such as Dante,

Liliana, Danza de los ojos verdes, Danza gitana,

and Suite sobre cantos gallegos.

Without doubt, the Tonadillas are

among Granados's greatest works. For Antonio Fernández-Cid,

the Tonadillas are "the most perfect achievement,

the most mature and refined, the most personal of all [the

works] which carry the signature of Enrique Granados."5

In Apuntes para mis obras, Granados

explains something of the importance he attached to his

Tonadillas:

[The] collection of Tonadillas [is]

written in the classic mode (originals). These Tonadillas

[are] originals; they are not those previously known

and harmonized. I wanted to create a collection that would

serve me as a document for the Goyescas. And it

has to be known that with the exceptions of Los requiebros

and Las quejas, in no other of my Goyescas

do you encounter popular themes. They are written

in a popular style, yes, but they are originals.6

In Apuntes para mis obras, Granados

compiled a list of Tonadillas he had written up

to that time. They were:

- La maja de Goya

- El majo discreto

- El tralalá y el punteado

- La maja dolorosa (1)

- La maja dolorosa (2)

- La maja dolorosa (3)

- El majo tímido

- El mirar de la maja

Of the Tonadillas he listed,

Apuntes para mis obras contains sketches for five

which he later completed: El tralalá y el punteado,

La maja dolorosa (1), La maja dolorosa

(2), La maja dolorosa (3), El majo tímido,

and El mirar de la maja. There are also sketches

for two that he never completed, El amor del majo

and El garbo, as well as poems and a brief untitled

musical sketch that corresponds to Las currutacas modestas.

The sketches for the Tonadilla El tralalá

y el punteado are placed by the composer on facing

pages. The verses appear on the left-hand page and the score

on the right. Granados's verses are as follows:

Si vienes de nadie y solo

Ven pronto y armado

Que los hombres de esta tierra

Son todos muy malos.

Ay tra la la la la la

La la la la la la la

Mira que no te deslices.

Tra la la la la la la

Mira que no te den paliza

porque puede ser que te den.

Tra la la la la la la.

The published version of El tralalá

y el punteado contains a totally different text, by

Fernando Periquet. Nevertheless, Granados's musical sketch

is virtually identical with the published version, lacking

only the four-measure introduction found in the published

version. Periquet's text follows:

Es en balde, majo mío,

que sigas hablando,

porque hay cosas que contesto

yo siempre cantando.

Por más que preguntes tanto,

en mí no causas quebranto

ni yo he de salir de mi canto.7

The music for La maja dolorosa (No.

1), which is known in the published version as No. 2, differs

from the published version only in details of notation.

Granados's sketch for the text, which appears in Apuntes

para mis obras on the facing page, is quite different

from the published version by Periquet. Granados's text

for La maja dolorosa (No. 1) is:

Majo de mis amores

que fue de tu vida?

Pobre majo

de mis amores!

Muerte traidora

se me llevó el alma mía

Ay, mi pobre vida!

Periquet's text for the published version of

La maja dolorosa (No. 1) follows:

¡Ay majo de mi vida,

no, tú no has muerto!

¿Acaso yo existiese

si fuera eso cierto?

¡Quiero loca

besar tu boca!

Quiero segura

gozar más de tu ventura.

Más ¡ay! Delirio, sueño,

mi majo no existe;

en torno mío el mundo

lloroso está y triste.

¡A mi duelo

no hallo consuelo!

Mas muerto y frío

siempre el majo será mío.

For La maja dolorosa (No. 3) in Apuntes

para mis obras , Granados prepared a set-up of staves,

clefs, and a key signature of three sharps. However, not

one note of music was written. The facing page contains

the black ink drawings titled La maja dolorosa, La maja

en el balcón , and the untitled self-portrait.

On a separate page, above the indication Hecha la letra

[Text completed], Granados wrote the following text

titled La maja dolorosa (No. 3):

Mi vida triste

Llena de dolor y recuerdos

Se ha resignado .

Y voy llorando

Recordando al bien amado

Y de mi llanto

Voy viviendo ahora sol

En mi dolor.

(Hecha la letra)

In spite of Granados's notation (Hecha

la letra), Periquet's text for the published version

of La maja dolorosa (No. 3) is completely different:

De aquel majo amante que fue mi gloria

guardo anhelante dichosa memoria.

El me adoraba vehemente y fiel,

yo mi vida entera di a él.

Y otras mil diera si él quisiera,

Que en hondos amores martirios son flores.

Y al recordar mi majo amado

van resurgiendo ensueños

de un tiempo pasado.

Ni en el Mentidero ni en la Florida

majo más majo paseó en la vida.

Bajo el chambergo sus ojos vi

con toda el alma puestos en mí,

que a quien miraban enamoraban,

pues no hallé en el mundo mirar más profundo.

Y al recordar mi majo amado

Van resurgiendo ensueños

de un tiempo pasado.

Granados's sketch for El majo tímido

in Apuntes para mis obras is not complete.

However, the music, as notated there, does not differ significantly

from the final published version, although, as in the case

of El tralalá y el punteado, the introduction

found in the published version is not present in this manuscript.

Granados's text for El majo tímido appears

on the page facing the musical sketch in Apuntes para

mis obras:

Se de cerca no te veo

que quieres que diga.

No si eres guapo o feo

Acércate, lila.

¡Ay que tímido!

¡Ay que tímido!

No se acerque señor majo

que a mi no me engaña.

No se acerque señor majo

que yo no le quiero.

Si creyó que le esperaba

no es mi pensamiento.

¡Ay que tímido!

¡Ay que tímido!

No se escurra el señor majo

que no le creo.

Periquet's text for the published version of

El majo tímido follows:

Llega a mi reja y me mira

por la noche un majo

que en cuanto me ve y suspira

se va calle abajo.

¡Ay, que tío

más tardío!

Si así se pasa la vida

estoy divertida.

Si hoy también pasa y me mira

y no se entusiasma,

pues le suelto este saludo:

Adiós, Don Fantasma.

¡Ay, que tío

más tardío!

Odian las enamoradas

las rejas calladas.

Granados's sketch for another Tonadilla,

El mirar de la maja, in Apuntes para mis obras

does not differ significantly from the published version.

This sketch includes sixteen measures identical to the corresponding

measures of the published version. However, there are an

additional nine measures, the final measures of the sketch,

which lack the piano accompaniment. The text is only hinted

at by three brief phrases.

In Apuntes para mis obras, intermingled

with sketches for Ovillejos, Granados wrote three

measures of music that are not titled or identified in any

manner. These three measures, in ex. 6, are clearly a sketch

for the Tonadilla, Las currutacas modestas.

Ex. 6: Granados, sketch for Las currutacas

modestas

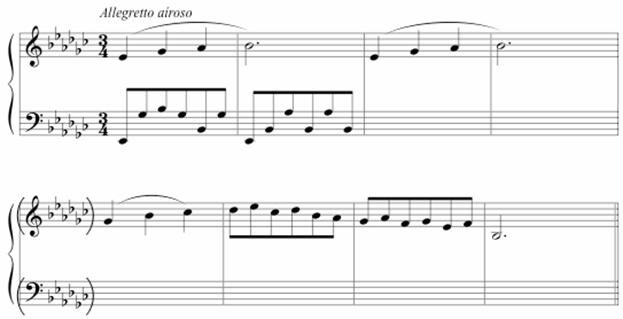

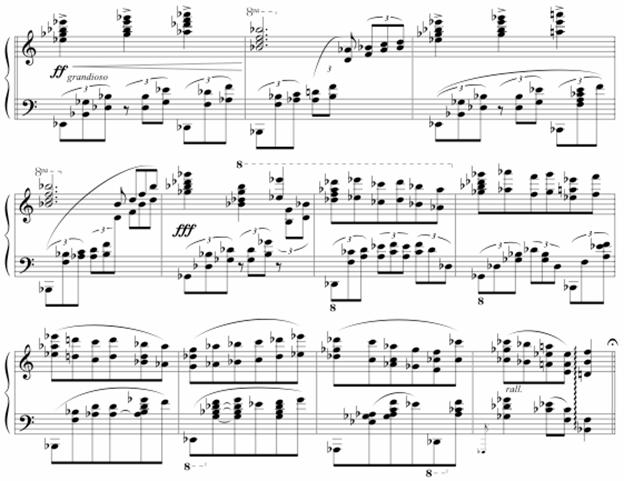

The sketch in ex. 7 for the projected Tonadilla

El amor del majo is decidedly similar to a portion

of Coloquio en la reja from the piano suite Goyescas.

Ex. 7: Granados, sketch for El amor del

majo

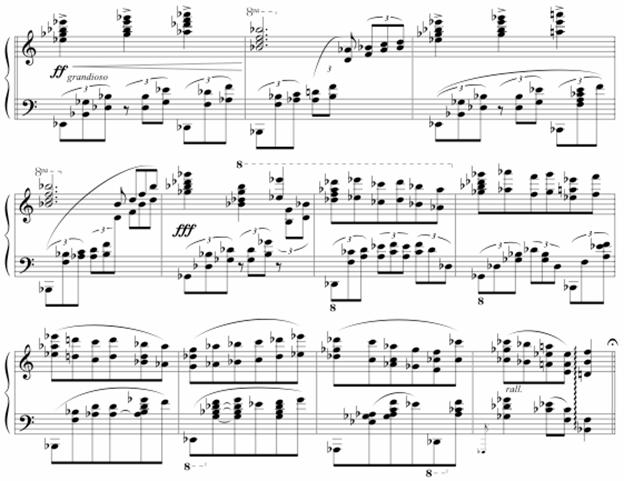

Compare the melody of El amor del majo,

ex. 7, with ex. 8, from Coloquio en la reja, mm.

166-76.

Ex. 8: Granados, excerpt from Coloquio en

la reja, mm. 166-76

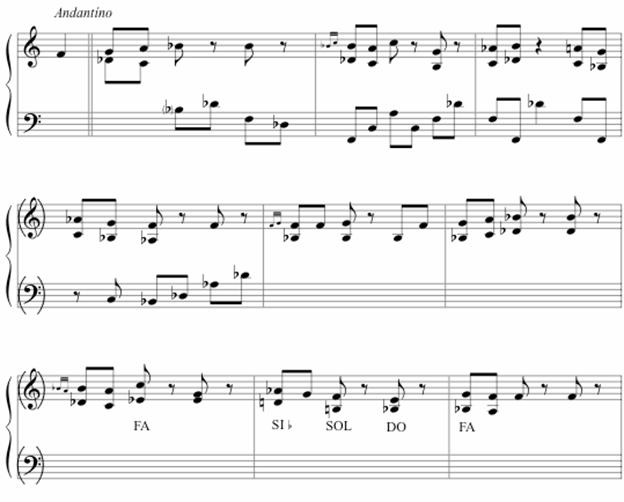

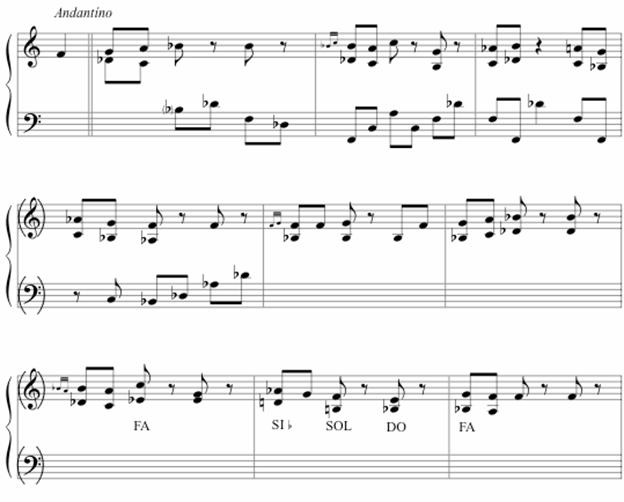

The sketch in ex. 9, titled El garbo,

however, does not appear to have a relationship to any of

Granados's completed works. In the last line of the sketch,

Granados indicated the harmonies to be used by the indications:

Fa, Si bemol, Sol. Do, Fa, without actually writing

the accompaniment.

Ex. 9: Granados, sketch for El garbo

In Apuntes para mis obras, Granados

wrote two untitled texts that are not related to specific

works. Both of these texts, presented below, appear to be

possible texts for other Tonadillas. The first

of these is:

Con garbo y con donaire

Va el majo galán

Va el majo galán

Pasito a paso por la pradera

Va por la pradera

The words of the first line of this text were

later used by Granados as an expressive indication in Los

requiebros from the piano suite Goyescas: Con

garbo y donaire. The second untitled text in Apuntes

para mis obras was written upside down:

Los majos que a mi me quieran

han de ser de la sal y pimienta

Por eso lo quiero yo

y yo los quiero tanto.

Por eso los quiero

llamando al portal.

Los llamo y los quiero

con todo mi amor.

¿ Porque no me digan

que soy de rigor?

Y digo que si,

que!

no!

Eso mismo digo yo.

As a whole, Granados's Tonadillas

have a melodic grace and a directness of expression that

are immediately captivating. The vocal melodies are completely

natural and of a simplicity that only the most refined artistic

personality could conceive. The piano accompaniment, which

frequently imitates the guitar, surrounds the voice, supporting

but never overwhelming the exquisite delicacy of the vocal

lines. José Subirá believed that in the Tonadillas,

Granados's achievement in capturing the spirit of the eighteenth

century and transforming it into his own musical language,

without loosing any of the original attributes of the era,

created an entirely new genre, "un genuíno

lied . . . a la española' [A genuine lied

. . . in the Spanish style].8

Frank Marshall, Granados's disciple, believed

that "Granados created the Tonadillas complete,

or in other words, [he created] the literary part and the

musical part at the same time." 9

The musical sketches and the verses for the Tonadillas

found in Apuntes para mis obras appear to

bear out this opinion, at least in part. For example, three

of the sketches for Tonadillas for which Granados

wrote both music and texts in the manuscript are considerably

developed, although none is a definitive version. When we

consider that the music Granados composed for the Tonadillas,

as notated in Apuntes para mis obras, is substantially

similar to the final versions, it seems likely that at some

point Granados must have realized that the texts he had

sketched in the manuscript were not of a comparable level

of artistic merit as his music. Thus, he abandoned them

and turned to Fernando Periquet to write the definitive

texts.

Therein lies one of the revelations of Apuntes

para mis obras: in two of his greatest works, the Tonadillas

and the opera Goyescas, Granados appears

to have broken with the standard practice of composers who

normally compose their music to fit an author's text. The

sketchs in Apuntes para mis obras indicate that

since the music for the Tonadillas was largely,

if not entirely, complete by the time Periquet began writing

the texts, it would appear that Granados left Periquet to

write a text for a pre-existing score. Similarly, only a

few years later Granados and Periquet followed this highly

unorthodox procedure when writing the opera Goyescas.

As early as 1912, Granados was working on the

score of the projected opera Goyescas. In the piano

suite Goyescas, Granados had already written a

considerable amount of music that he was to use in the opera.

However, he lacked a libretto. Not surprisingly, he turned

to Fernando Periquet.

The story of the writing of Goyescas is

well documented. Periquet explains that the score of the

opera was composed in a particularly unusual manner. He,

Periquet, wrote a narrative poem based on the final plot,

which he submitted to Granados. Referring to this text Periquet

told Opera News: ". . . not intending that the

musician should set my verse to music but that Granados

might let his fancy roam over the scenes and stories I had

built of my rhymes. So was his charming score composed,

without words, in the most absolute freedom, while seeing

in his imagination a gorgeous pageant of Goyesque figures."

10

After the music was written, Periquet was given the almost

impossible task of creating a libretto that would fit the

music.

Periquet describes the difficulty: "When

the last note of his music was set down there fell on me

a hard . . . task, a painful tour de force, . .

. I had to write new words for the music! What I wrote for

Granados's music were [sic] not, could not be verse. The

speeches of the characters had to follow, note by note,

the maestro's fantasy. The rhymes were exotic,

the rhythms irregular."11

Periquet's description is certainly accurate

in that the text could not be considered as verse. By any

standard the libretto is crude. Many critics have observed

that the method adopted by Granados and Periquet of affixing

the libretto to the already composed score did not achieve

a convincing result, and not surprisingly, Periquet's libretto

received much merited criticism following the premiere of

the opera in January 1916. A review published in The New

York Herald Tribune described the problem: "There

can be no doubt that the librettist in his effort to affix

words to Granados's music was led more by his intention

to supply a word for each note than by the dramatic demand

to express the meaning of the music in appropriate language.

By this crowding of words to short notes the vocal parts

become instrumental, . . . and the singer cannot do justice

. . . to the effectiveness of the vocal part as against

the orchestra."12However,

no such criticism can be applied to the Tonadillas.

It is likely that in creating both the Tonadilllas

and the opera Goyescas, Granados and Periquet

followed a similar procedure in each case by adding a text

to previously composed music. Nevertheless, the quality

of the result in the two instances is markedly different.

In the Tonadillas the music and text converge

in a work of undisputed genius while in Goyescas,

unfortunately, the text only rarely illuminates the music.

Many writers have noted that Granados was directly

inspired by specific works of Goya, specifically by Goya's

Caprichos, Tal para cual, and El amor y la

muerte, as well as by specific paintings such as El

pelele. Yet it was more than specific works by Goya

that fascinated Granados. Granados was less inspired by

Goya's art itself than by his own fantasy of Goya. It was

the atmosphere, the people and the details of their lives

within the context of Goya's Madrid , which spoke to the

composer. Granados stated that in the Tonadillas he

had created a collection that would serve him as a "document." Perhaps this music sets the atmosphere for Goyescas,

and the texts tell in words something of the situations

and actions of the type of people he had in mind when writing

Goyescas. When considered as such, the Tonadillas

along with the drawings found in Apuntes para

mis obras clearly illustrate the extent of Granados's

inspiration by and devotion to the works of Goya. This highly

personal inspiration, shown so vividly in this manuscript,

led Granados to compose some of the greatest works ever

written in Spain.

Most composers tend to confine their manuscript sketches only

to music. However, in Apuntes para mis obras Granados

reveals himself as a complete artist, coalescing his inspiration

by one of Spain's greatest painters through poetry, graphic

arts, and his own highly personal music.13

1

Consejos a los alumnos: Deben estudiarse con preferencia

las obras que mejor se saben.

2

El mecanismo se compone de fuerza, igualdad

y agilidad. / ¿Qué contribuye a la fuerza?

/ La articulación. / La posición del cuerpo,

brazo y mano. / ¿Qué contribuye a igualdad?

/ Equilibrio de fuerza por igual en todos los dedos. / ¿Qué

contribuye a la agilidad? / La supresión de todo

movimiento inútil.

3

Enrique Granados in "True History of the Goyescas,"

Francisco Gándara, Las novedades (New York),

April, 1916, 12-13.

4

Canto expresivo con oboe y cornetín tocando

piano. Combinado la cuerda, mitad pizicato / [sic],

mitad arco, contra puntístico en los altos y

con sordino. / Dibujos de flauta junta con cuerda en sordino.

/ Cornetín fragondo en la tesitura alta, fa, sol,

la bemol. Con insistencia. / Flauta tocando piano en registro

medio, combinada unisón con fagot, 2 octaves de distancia.

/ Clarinete doblando ligato [sic] y piano un dibujo

de escasa pasamiento, pizicato [sic] de la cuerda

y arpa. / Flauta y lira y cuerda en lo alto. / Violines

en la cuerda alta junto con la voz de timple y a veces doblando

por una tromba a la 8 baja.

5

". . . el mas perfecto logro, el mas sazonado y redondo,

el mas personal entre cuantos llevan la firma de Enrique

Granados." Antonio Fernández-Cid, Granados

(Madrid: Samarán Ediciones, 1956), 223.

6Colección

de Tonadillas escritas en modo clásico (originales).

Estas tonadillas originales, no son las conocidas anteriormente

y armonjadas. He querido crear la colección que me

sirve de documento para la obra Goyescas. Y ha de saberse

que a excepción de Los requiebros y Las quejas en

ninguna otra de mis Goyescas se encuentra temas populares.

Hecho en modo popular, sí, pero originales.

7

All texts by Periquet are quoted from Enric Granados, Integral

de l'obra per a veu i piano, ed. Manuel Garcia Morante

(Barcelona: Tritó, 1996).

8José

Subirá, "Granados tonadillero," in Enrique Granados,

Revista Musical Hispano-Americana (Madrid), April

30, 1916, 16-17.

9

". . . Granados ideó las Tonadillas completas, o

sea la parte literaria y la musical a un tiempo." Frank

Marshall in Fernández-Cid, Granados, 223.

10

Fernando Periquet, "Goyescas: How the Opera Was

Conceived," Opera News, January 29, 1916, 12.

11

Ibid.

12 "Goyescas, Spanish Opera: Brilliant Music, Not

Dramatic," New York Herald Tribune, January 29,

1916 .

Portions of this text were originally published as "El llibre d'apunts d'Enric Granados," Douglas Riva, trans. Joan Malaquer i Ferrer, Revista de Catalunya , n26 (January 1989): 89-106. |